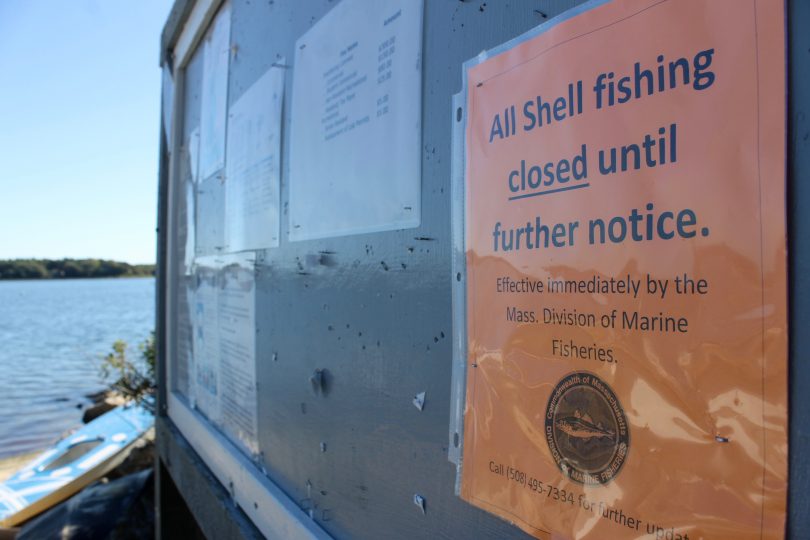

“This is definitely new for all three states,” said Michael Hickey, chief biologist for the shellfish program for the State Division of Marine Fisheries.

“Yeah, it’s worrisome,” said Hickey. “It may be the beginning of a trend that’s going to have an adverse affect on the shellfish industry, and could potentially be harmful to people’s health. I’m not happy about it. Let’s put it that way.”

“Yeah, it’s worrisome.” – Michael Hickey, chief biologist for the shellfish program for the State Division of Marine Fisheries.

The Massachusetts closure is in effect for the south shore of Cape Cod, he said, as well as Martha’s Vineyard and Nantucket, said Hickey. Cape Cod Bay is not affected, he said.

The closure is a precautionary measure as the state awaits test results from a private lab in Maine on shellfish and phytoplankton taken from several locations, said Hickey.

Shellfish at Falmouth Fish Market. The state is confident that all shellfish already harvested is safe.

“The testing technique is sophisticated and expensive,” he said. “Most state labs don’t have the ability to perform this test.” Rhode Island and Maine have sent samples to the same private lab, he said.

“We’re concerned about the toxin levels in the shellfish,” said Hickey.

“Rhode Island discovered that they had a big bloom in Narragansett Bay last Wednesday (October 5),” said Hickey.

On October 6, “They called us. We talked about it. We compared notes on how to deal with it. There was toxicity in some of the tests they were doing on the plankton,” he said.

“We share a body of water, Mount Hope Bay. They closed Mount Hope Bay on October 7, said Hickey. Massachusetts did the same. “Realizing what was going on in Narragansett Bay, we knew we better be looking at Buzzards Bay. And that continued throughout the weekend sampling Vineyard Sound, Nantucket Sound,” he said.

“It’s certainly new around here,” said Hickey of the toxin associated with the phytoplankton.

The phytoplankton is called Pseudo-nitzchia, but it is more complicated than than that. “There are a number of species of pseudo-nitzchia,” he said. “That is the genus name. The second name is the species.”

Hickey named off several species of Pseudo-nitzchia. “Fourteen species are found off the coast of New England. Four can produce a toxin. The ones that produce the toxins don’t always produce the toxins,” he said.

“Simply having a toxic species present is not enough to say they are definitely making these toxins,” said Kate Hubbard, a research scientist at Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission and a guest investigator at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution as part of the Woods Hole Center for Oceans and Human Health.

“In order to have a toxic bloom, you have to have the toxic species as well as conditions conducive to producing the toxin,” said Hubbard.

Scientists are trying to find out what those conditions are, she said.

Samples taken in Massachusetts waters show that cell counts of the phytoplankton are very high, said Hickey. “We measure cell counts by the number of cells in a liter of water. Fifteen thousand cells in the water isn’t very shocking… but we’re up to a million,” he said.

“The size of the bloom and the numbers of cells per liter, and the producing of toxicity in Rhode Island shellfish and in Maine, and the toxicity levels in the plankton in Narragansett Bay is unprecedented,” said Hickey.

He does not know how long shellfish beds in Massachusetts will remain closed.

“The best parallel for this is probably eastern Canada,” said Hubbard. “The first Amnesic Shellfish poisoning event ever occurred in 1987. Since then, there have been many closures. Sometimes there have been closures in many areas. Sometimes, there have been closures a few years in a row. And sometimes, a few years go by and nothing happens,” she said.

“We’ve had the first closure in New England because of this toxin in Maine this year,” said Hubbard. “There’s been precautionary closures in the past. This is the first true closure.”

Hubbard said, “The first documented event was on Prince Edward Island. There were a few fatalities and a number of people got sick. Since then, nationally and internationally, there’s been a concerted effort to test shellfish.”

“That’s thousands of dollars of shellfish that I can’t buy.” – David Shahzade, owner of Falmouth Fish Market

Hickey said the toxin is found on the west coast, off Washington and Oregon, and “has been spreading over time for the last 30 years. There’s a lot of theories. Nobody really knows why. A lot of things going on have to do with climate change and global warming, but pseudo-nitzchia tend to like colder water,” said. Thus, this bloom is even more confusing to understand, he said.

David Shahzade, the owner of Falmouth Fish Market said it was a very hot summer and fishermen complained to him of the warmer waters, causing them to catch less bluefish, striped bass and tuna than usual.

Shahzade said he has been in business for 28 years and he’s never encountered this particular reason for a closure of the beds before. There has been red tide, but never this particular phytoplankton, he said.

Asked about closures, Hickey said, “The economic impact can be huge.”

“We buy from several fishermen, up to a dozen guys, maybe 15,” said Shahzade. “The average fisherman, can make 150 to 200 dollars a day. The hard-core heavy hitters make 300, up to 400 a day,” he said. “So that’s thousands of dollars of shellfish that I can’t buy.”

There are, of course, many fish markets on Cape Cod, each buying from many fishermen.

Shahzade said he sells to other dealers, restaurants all the way up to Boston. In his store, he still had some in stock.

Hickey said, “We’re pretty confident, both us and the Department of Health, that anything that has already been harvested is safe.”

Please like us on Facebook.