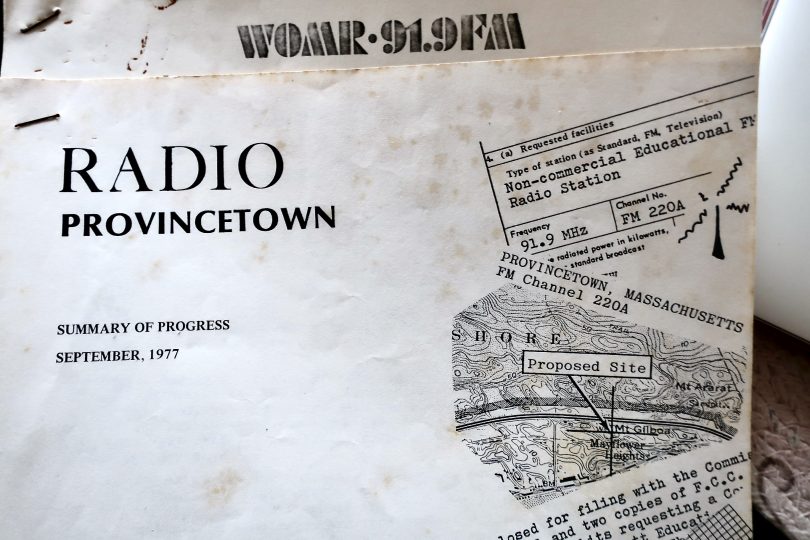

PROVINCETOWN – Starting a community radio station on the Outer Cape was an audacious idea that first appeared in 1976 as a spark inside the mind of Mark Primack, a “professional hippie” living in Provincetown at the time. “I had never really accomplished anything,” said Primack, 74, who now lives in New Hampshire. “I was…

You may also like

Happy Fourth of July – It all feels so… “normal” – an Essay

Foggy Evening in Woods Hole – Slide Show

Sarah Burrill: “Rise Above” at the CC Women’s Music Festival – Music VIDEO

ArtsCape: Please Touch (the Art!) at Cotuit

Harvest Days: Remembering Michael Pearson’s Harvest Gallery Wine Bar

The Grab Brothers Make Hippie Happy Music – A Profile

A Paywall For Our Longform Stories

“No Kings” Protests in Falmouth & Provincetown – VIDEO + ESSAY

Spontaneous Collaboration: Jackie Reeves and Lauren Wolk’s InkLine Project

Smoke Stack lightning: ‘Sinners’ sizzles – Play It Again, Tim

Spies play cat-and-mouse in ‘Black Bag’ – Play It Again, Tim

RIP Bruce Maclean – “the last old-time freak”

A suggested Hackman fest, an Oscar recap and a tardy review – Play It Again, Tim

Ho-hum, Oscar night at last–Play It Again, Tim

The “Functional Art” of Walter Baron, Boatbuilder – A Profile

‘Wolf Man’: Toxic masculinity strikes again – Play It Again, Tim

Singer a simian sensation in ‘Better Man’ – Play It Again, Tim

‘Bikeriders,’ ‘Beast’ best of the best for 2024 – Play It Again, Tim

Catching up during awards season; Play It Again, Tim

Follow The Money, and The Good Vibe; Why Shop Local – An Essay

Duo brings Y2K scare back to life in horror comedy

Making Things Happen; Attorney Bruce Bierhans – A Profile

Atlantic White Cedar Swamp Trail + Marconi Station Site – Slide Show

Sunset At The Knob – Slideshow

‘Here’ a forced tale of space and time–Play It Again, Tim

Bourne Farm, West Falmouth – Slide Show

Cardinals ask, ‘Who’s next?’ in ‘Conclave’–Play It Again, Tim

Cranberry Harvest In North Falmouth – Slide Show + VIDEO

The “Y” in the road; Another “Most Important Election Of Our Lifetime” – An Essay

3 Minutes Of Running Water Zen at Four Ponds Conservation Area – VIDEO

About the author

Brian Tarcy

Brian Tarcy is co-founder of Cape Cod Wave. He is a longtime journalist who has written for the Boston Globe, Boston magazine, the Cape Cod Times and several other publications. He is the author of "YOU CAN'T SELL RIGHT FIELD; A Cape Cod Novel." He is also the author or co-author of more than a dozen mostly non-fiction books, including books with celebrity athletes Cam Neely, Tom Glavine and Joe Theisman. His previous book was, "ALMOST: 12 Electric Months Chasing A Silicon Valley Dream" with Hap Klopp,who created the iconic brand, The North Face.

For more information, see Briantarcy.com

Brian is a long-suffering Cleveland Browns fan with a long-running NFL predictions/political satire column connecting weekly world events to the fate of his favorite team, now at Whatsgonnahappen.com.