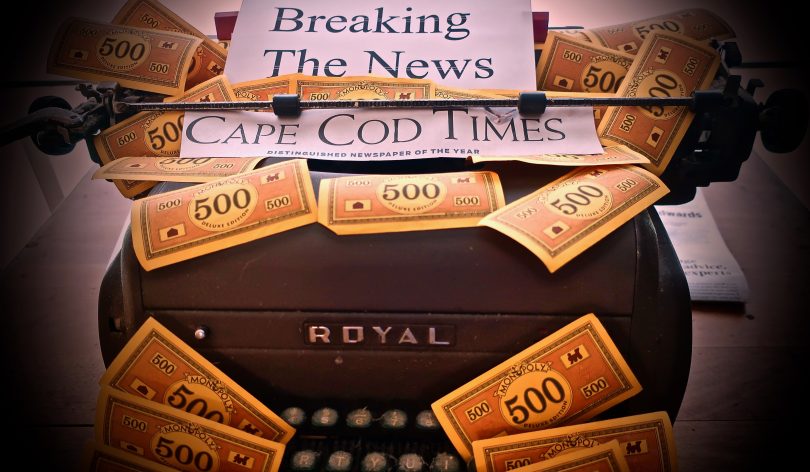

CAPE COD – In May, shortly after longtime editorial page editor Bill Mills was laid off and not replaced at the Cape Cod Times, the paper announced “a new tradition” to no longer publish daily editorials. That month the paper, owned by Gannett, laid off three seasoned journalists, including Mills, who had a combined 85 years…

You may also like

Frozen Out: As ICE Acts on Cape Cod, Locals React

A Paywall For Our Longform Stories

Four Sportswriters, Boston’s Mount Rushmore, Go To A Cape League Game: SLIDE SHOW + Essay

Happy Fourth of July – It all feels so… “normal” – an Essay

Harvest Days: Remembering Michael Pearson’s Harvest Gallery Wine Bar

The Grab Brothers Make Hippie Happy Music – A Profile

“No Kings” Protests in Falmouth & Provincetown – VIDEO + ESSAY

RIP Bruce Maclean – “the last old-time freak”

The “Functional Art” of Walter Baron, Boatbuilder – A Profile

Follow The Money, and The Good Vibe; Why Shop Local – An Essay

Making Things Happen; Attorney Bruce Bierhans – A Profile

The “Y” in the road; Another “Most Important Election Of Our Lifetime” – An Essay

Are We Winning? In Our Summer Paradise, Summer Is Warmer & Longer

Dream Job: Rich Rogers’ Blue Collar Path to WMVY – A Profile

Happy? Fourth Of July – An Essay

Wear A Cape Cod Wave Hat Near Cape Cod Waves

Christmas Cavalcade For The Homeless Set For December 17 At The Music Room In Yarmouth

Looking Back – 10 Stories, 10 Years

My Dream 10-Year Anniversary Concert That Did Not Happen

Cape Cod Wave Magazine is 10 Years Old

Dan McKeon: Ptown’s Available Housing Matchmaker – A Profile

Mwalim: Da Phunkee Professor, Artist, Writer & Groovalotto – A Profile

Martha’s Vineyard, Political Symbol – An Essay

Zoe Lewis: Provincetown’s Jazzy Zen Vaudeville Vagabond – A Profile

Eradicating Racial Wealth Gap Theme for Hyannis Event

ArtsCape: The Quirky Creations of Sue Beardsley

George Sylvestre, Fishing The Brewster Flats – A Guide’s Story

Andy Dufresne: 91 Candles For Falmouth’s Civic-Minded Barber – A Profile

Cape Cod Wave Magazine is 9 Years Old!

WOMR At 40; An Outermost Radio Tale of Audacity & Tenacity

About the author

Brian Tarcy

Brian Tarcy is co-founder of Cape Cod Wave. He is a longtime journalist who has written for the Boston Globe, Boston magazine, the Cape Cod Times and several other publications. He is the author of "YOU CAN'T SELL RIGHT FIELD; A Cape Cod Novel." He is also the author or co-author of more than a dozen mostly non-fiction books, including books with celebrity athletes Cam Neely, Tom Glavine and Joe Theisman. His previous book was, "ALMOST: 12 Electric Months Chasing A Silicon Valley Dream" with Hap Klopp,who created the iconic brand, The North Face.

For more information, see Briantarcy.com

Brian is a long-suffering Cleveland Browns fan with a long-running NFL predictions/political satire column connecting weekly world events to the fate of his favorite team, now at Whatsgonnahappen.com.