PROVINCETOWN – Once upon a time, Tennessee Williams was young and beautiful and in love in Provincetown. He stayed at Captain Jack’s Wharf in the West End, where he listened to the rhythm of the tide as he wrote “The Glass Menagerie” on a borrowed typewriter.

This week, for the tenth year, Provincetown is remembering that time and all of the work of Williams, a writer that David Kaplan, curator and co-founder of the Provincetown Tennessee Williams Theater Festival, compared to the eternal greats, including William Shakespeare.

“The words are incantations,” said Kaplan. “They are recipes for magic.”

“Really, this is what it’s about,” said Kaplan. “Love and beauty and youth pass very quickly so there is an imperative to remember them, and because they pass so quickly they are that much more important. That’s what Tennessee Williams was about.”

Tennessee Williams is back in Provincetown.

In many ways, said Kaplan, the spirit of Tennessee Williams has always been alive in Provincetown. “You’re at the edge of the Earth, where the Earth meets the sea. Where solid becomes liquid.” It represents, he said, “the changeability of moving between worlds and consciousnesses.”

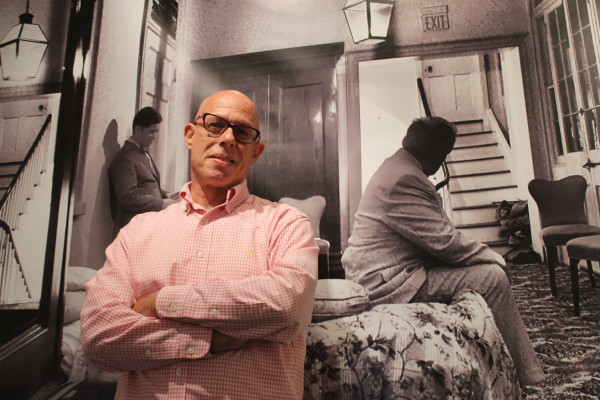

Kaplan, a fifth generation Manhattanite, is a part-time resident of Provincetown. He is an international theater director, the author of two series of college textbooks for actors, and he is the author of “Tennessee Williams in Provincetown” (2006; Hansen Publishing Group).

Kaplan also creates art installations, including “The Hotel Plays,” currently at the Berta Walker Gallery in Provincetown. “The Hotel Plays” features moody photographs of actors backstage at a Tennessee Williams Festival in New Orleans.

Williams wrote, said Kaplan, “memory plays… All of us know the power and warmth of memory, and that’s what Williams celebrates,” he said.