PENIKESE ISLAND – The huge black-backed seagulls squawking on Penikese Island do not like to be disrespected. They will fight to kill, as a giant seagull carcass near a walking path made clear. (See story on the school re-opening.)

There are ghosts on the island too. “It’s haunted,” said Ben Heiken, 27, who spent almost two years as a student at the Penikese Island School. From 2002 to 2004, Heiken lived on the isolated island, 12 miles off the coast of Woods Hole. He heard footsteps in the middle of the island, when no one was near. Saw a man sitting on a rock, and then the man was gone. “That place is haunted,” he said again.

On Penikese Island, where troubled boys went for 38 years for a chance at redemption, the birds are mean. Territorial. “Hitchockian,” is how Carl Lovejoy, Director of External Affairs of the Mountain Valley Treatment Center, the sister program of the newly reopening Penikese, described the birds. This, after all, is their neighborhood. The kids coming out here for all these years have understood that concept.

And the ghosts? It would seem that the former residents of the leper colony, closed in 1921, might be the top suspects.

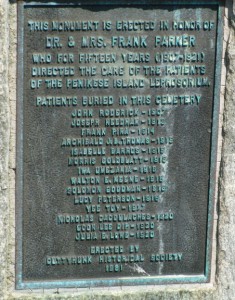

The buildings of the leper colony, on a different side of the island than the school facilities, were burned and dynamited after the colony closed. Some residents of the colony, which was open for 16 years, died on the island. Their burial ground is up a walking path, past the birds, at one end of the long, thin 75-acre island. Death, also, was a concept all too familiar to many of the past students of the island.

Territorial birds and an occasional ghost are just part of the experiential learning process that Penikese has been offering, and will offer again, to try to heal troubled boys. When the facility reopens this summer, the boys living out here will be facing different issues than those sent here previously. Some of the program will be different too.

“What’s special about the island is the island,” said Jim Newman, Chairman of the Penikese Island School Board of Directors. “A magic kind of therapy can happen on that island.”

Near the end of the chain of the small Elizabeth Islands that extend southwest from Woods Hole, Penikese Island is 12 miles out to sea and 100 years back in time. “It’s not unlike an 1800s way of life,” said Lovejoy. There will be generators out there now for some electricity to power computers for classroom work. But there will still be plenty of chores for the kids to do to survive on the island.

“When you first get dropped off on that island and that boat drives away, it’s pretty intimidating,” said Shawn Campbell, 31, who spent time as a student in 1999 on Penikese. Like many new arrivals, forced to choose between Penikese and jail, he didn’t show up with a great attitude to the staff. “My first day out there, I looked right at [a staff

member] and said, ‘Fuck you,’ and kept walking,” said Campbell.

“My first night out there, laying on a strange bed on a strange island, I spent three hours contemplating what my future might be like,” said Campbell.

Heiken said, “I cried my first night out there. It felt like jail.”

But Heiken, now a carpenter living in Cumberland, Rhode Island, also felt something else. “My first couple of days, I fell in love,” he said. “Penikese Island, when you get out there, you are instantly greeted with love.”

Not all recognize that.

“It took me a month or two to understand that I had the opportunity to change my life,” said Campbell, who is now the maintenance supervisor of a timeshare resort in Falmouth.

A Most Fascinating History

At only 75 acres, Penikese “is the smallest of the Elizabeth Islands, but has the most fascinating history of all of them,” said Toby Lineaweaver, the director of operations of the new program and the former executive director of the old program. Lineaweaver spent 15 years working on the island, and now he is back.

“I love the island,” said Lineaweaver. “It’s beautiful, adventurous, remote. It brings people incredibly close together. It helps you understand and see things about yourself. It slows you down and helps you to let go of what’s not important.”

The island is certainly a therapeutic place. It seems to have always been that way. But it’s been, and remains, so much more than that. Between 1873 and 1875, the naturalist Louis Agassiz used the island to open the Anderson School of Natural History, which was the predecessor to the Marine Biological Laboratory in Woods Hole.

In many ways, the island has remained a laboratory ever since.

Between 1904 and 1921, Penikese Island was operated by the state as a leprosy hospital.

The island became recognized as a wildlife sanctuary, especially for several species of ground nesting birds, many of which had become endangered. From the 1920s to the 1940s, there were caretakers on the island. There were experiments with possible uses, said Lineaweaver, including rabbit farming.

During World War II, the caretakers were cleared off of the island. Penikese only had occasional caretakers until the early 1970s, said Lineaweaver, when an ex-Marine named George Cadwalader came up with the idea of opening a school for troubled boys on the same island that had once housed a leprosarium.

The state agreed to allow the school to be built on the footprint of the former buildings of the Anderson School, said Lineaweaver. The island is owned by the state and run by the Massachusetts Department of Wildlife, which manages the bird sanctuary.

The school, said Lineaweaver, serves as caretaker for the island. Lineaweaver said the school actively supports the wildlife management projects, including transporting personnel and supplies on the school’s 36-foot workboat, the Richard S. Edwards. “Everything we do has to be run by Mass. Wildlife for the potential impact on the birds,” said Lineaweaver.

According to Derek LaFlamme, Penikese Island Bird Sanctuary Manager, having the school for boys on the island is a “very mutually beneficial relationship.”

“It gives the kids one more opportunity to learn about something they didn’t even know they were interested in,” said LaFlamme.

“The sanctuary benefits from the school by it being a deterrent to the public to come to the island. “There are lot of birds nesting right there on the beach,” he said. “You can be walking along and not even realize there are eggs,” he said. The major concern is the piping plovers and the roseate terns, said LaFlamme.

The seagulls and crows are predators for the shorebirds and part of the job of the Department of Wildlife is predator control, including shooting predator birds.

The shorebirds are protected but in the middle of the island away from the beaches, menacing seagulls stalk the walking path that dissects the island. The birds are ready to attack if you don’t carry something like an umbrella above your head. There is one other reason for the umbrella, as former student Campbell can attest. It only happened twice in all his time on the island, he said, but “It felt like I was hit with a giant water balloon.”

“The Struggle Is Everything”

“One of our sayings on the island,” said Lineaweaver, “is the struggle is everything.”

Lineaweaver told the story of trying to get a kid to chop wood to heat the house where everyone sleeps, and the kid swearing at him and saying, “Make me.”. Penikese, after all, operates year round. Without wood, there is no heat. “So now I’ve got a power struggle on my hands, and I’m thinking, ‘Where the hell did that come from,’ “ he recalled.

“Some programs would solve that problem by using force,” said Lineaweaver. “On Penikese it’s much more important to figure out what’s going on and why. There’s never an obvious answer. It takes a lot of patience, it can be a little bit messy, and very indirect. In that struggle, people do the most growing and changing. The change is not formulaic in the Hollywood sense,” he said.

Campbell acknowledged that his change was slow evolving, and some kids never actually changed.

“Struggling teenagers aren’t very grateful,” said Lineaweaver. “They aren’t warm and fuzzy. They don’t make us feel good. They are not going to reward us by saying thanks.”

In fact, Penikese is not perfect. It does not solve every problem. Many of the boys who were treated there in the past have gotten into trouble afterward. The first sentence of the Preface to George Cadwalader’s book about Penikese, “Castaways” (Chelsea Green Publishing, 1988), is, “This is the story of an experiment that would appear to have failed.”

Jay Wolter, CEO of Becket Family of Services, which is partnering with the Penikese Island School to reopen Penikese, acknowledged that no program can get 100 percent success. “But in the short term, there is tremendous change.” And in the long term, for some, it sticks.

That’s what happened for Campbell. “I’m indebted to Penikese Island,” said Campbell. “I owe them my life.”

Campbell was born in New Bedford and raised in Fall River, where he was put in a series of foster homes starting at 9 years old. He got in trouble for “selling drugs, robbing cars, breaking into people’s houses.” This landed him in some juvenile lockups, including one that he ran from. He lived on the streets when he was 16 for six months until the weather turned cold and he turned himself in to DSS (now the Department of Children & Families).

He had to appear before a judge and was given a choice of the Springfield House of Corrections or the voluntary Penikese program. “I had heard nothing nice about Springfield,” Campbell said.

But when he arrived on Penikese and began his stay by cursing at a staff member, he was about to learn, slowly in a non-linear way, that Penikese was different. “Penikese breaks kids down and then rebuilds them,” said Campbell. “At Penikese, they live out there with you and they respect you. And you respect them.”

The island is special, sure. But it was the staff, more than the setting, that both Campbell and Heiken credited with transforming their lives. “On Penikese, those people are dedicated to helping kids,” said Campbell. “You have to be dedicated to be working out on Penikese. That’s not a 9-5 job. They are out there Monday to Friday, a whole week they live with you.”

Heiken, whose nickname is “Cuba” because he is Cuban, said the island is magical, a fantasy place, but “the staff made all the difference.”

Heiken, who said, “I’m the only Cuban-Jewish guy you’ll ever meet,” said he was adopted into a Jewish family, had some identity problems and ended up “running with gangs and doing the wrong thing. A judge offered me a choice between jail and this primitive island. I didn’t want to go to Penikese. But I went to the island, and I became a man.”

“I never read a book before I stepped on Penikese Island. Somebody came up to me and told me I had to read this great book. I said, ‘Nah, I’m all set.’ “ Turned out, though, that he reads all the time now, he said.

Penikese, said Heiken, was a place where he was faced with the question, “Do you have the guts to become a man?”

No Distractions

The island living part of Penikese sets it apart. But so does the 1800s life style. “We promote self-sufficiency,” said Lineaweaver. “They are not little birds in the nest with their beaks open waiting to be fed.”

In fact, said Lineaweaver, “Whatever challenges you have, you’re going to run into out there,” he said. “The staff has challenges as well as the students.”

There is an almost forced bonding. Work needs to be done in order to survive on a remote island 12 miles out to sea full of ghosts and real – not video game – angry birds. “In a remote and isolated therapeutic environment, everything is compressed and telescoped,” said Lineaweaver. “You are faced much more directly with a challenge to change your behavior.”

“The kind of person you are, the choices you make, what kind of issues you have all come quickly to the surface on Penikese,” said Lineaweaver. “It’s hard to run from the challenges. From a treatment perspective, it’s optimal.”

Campbell said, “The 18th century farm does help. There are no distractions.”

Instead, there is farming and fishing and billiards and “old school coffee,” said Heiken. “Hot water with a press, you press the coffee. Penikese Island coffee is the best coffee in the world.”

Heiken has a lot of great things to say about Penikese including, “the best day out there would have to be the day when the pigs escaped from their pen. We used to have four pigs out there in a pig pen. We could throw apples to them and they would eat the apples in one bite. Well one day, they escaped and we had to chase them all over the island,” he said.

Common Ground

“Being on an island like Penikese is unplugging,” said Lineaweaver. “It slows your own rhythms down to the point where you can be more attentive to the world within you.”

“When you’re sitting around the table and you’re just discussing things, it’s like living in a big family,” said Campbell.

But sometimes, in families, there are issues. “If the kids had a problem, the staff members said, ‘Go take a walk and settle it.’ That’s how we did it out there,” said Campbell. “When I left the island, I had respect for everybody. It was definitely the staff members being out there with you instead of just coming into work for a paycheck that made the difference.”

Lineaweaver explained that at the old school, kids often explained that they got in trouble by beginning a sentence with the words, “When people disrespect me…”

“Well, when they come to the island, they are going to run into times when they perceive, rightly or wrongly, that they are being disrespected. So the kid would respond with the only tool he had in his basket, to get pissed off.”

In fact, said Lineaweaver, many kids showed up on the island so wrapped up in their own issues that they were incapable of seeing what most adults see, a beautiful island. “They don’t see how beautiful it is. A kid’s brain doesn’t work like our brains work. The things that matter to us aren’t the same things that matter to them. One of the biggest disconnects in the world is treatment based on what we think would be helpful to a kid on the basis of how our brain works.”

Instead, on Penikese Island, said Lineaweaver, “we find common ground.”

Please like us on Facebook

For more stories like this, please see Longform stories

– A Novel By Brian Tarcy of Cape Cod Wave

A softball team called the Townies. A slick developer with a sketchy story. A town divided over a zoning change….— YOU CAN’T SELL RIGHT FIELD, A Cape Cod Novel